The GenX Exposure team has published an academic paper, “Measurement of novel, drinking water-associated PFAS in blood from adults and children in Wilmington, North Carolina” in the journal, Environmental Health Perspectives. “This paper shares the blood results from our Wilmington cohort,” explains Dr. Nadine Kotlarz, lead author on the paper and postdoctoral scholar for the project.

“There were a lot of people in addition to our Wilmington participants involved with this work: researchers from NC State University and Eastern Carolina University, community partners like Cape Fear River Watch, and numerous volunteers, and graduate and undergraduate students who all made this work possible. I’m glad that this research has advanced our understanding of PFAS exposures in the lower Cape Fear River Basin, NC because measuring exposure is the first step toward understanding potential health effects.”

Despite not being able to work in the lab due to the pandemic, the GenX Exposure Study team continues to do all they can maintain momentum. “Even though we’ve been working remotely, our team has continued to make progress on understanding PFAS exposure in North Carolina,” explains Dr. Jane Hoppin, Principal Investigator for the study.

“In our study process, after we present results to our participants through report back letters and community meetings, we write scientific papers and share what we’ve learned with other researchers. It’s exciting to have this paper published. These papers make our findings available to public health professionals to help evaluate the broader impacts of PFAS exposure. Even though we’re doing things behind the scenes now, the study continues to progress, and this paper is a great accomplishment for our study and everyone involved.”

You can read a summary of the paper below, and you can find the entire paper here.

“Measurement of novel, drinking water-associated PFAS in blood from adults and children in Wilmington, North Carolina.” Environmental Health Perspectives.

Nadine Kotlarz, James McCord, David Collier, C. Suzanne Lea, Mark Strynar, Andrew B. Lindstrom, Adrien A. Wilkie, Jessica Y. Islam, Katelyn Matney, Phillip Tarte, M.E. Polera, Kemp Burdette, Jamie DeWitt, Katlyn May, Robert C. Smart, Detlef R.U. Knappe, and Jane A. Hoppin

Background

In June 2017, Wilmington, NC, residents learned that a chemical called GenX was present in their drinking water. An upstream chemical facility had been releasing several per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), including GenX, to the Cape Fear River, the city’s primary drinking water source, since 1980.

About the GenX Exposure Study

The GenX Exposure Study was created to answer community questions about GenX and other PFAS, the main one being: “Are PFAS detectable in me?” In response, NC State and ECU researchers collected blood samples from 344 Wilmington residents (289 adults and 55 children) between November 2017 and May 2018. Additionally, 44 people had a second blood sample collected six months after their first one. The first sample was used to see what PFAS were present. The second sample was used to see how the levels changed in six months. All blood samples discussed in this paper were collected after the chemical company had stopped releasing GenX into the Cape Fear River. The study looked at both “fluoroethers,” new PFAS unique to the chemical plant, and “legacy” PFAS which have been used for decades (e.g., PFOA, PFOS).

Major Study Findings in this Paper

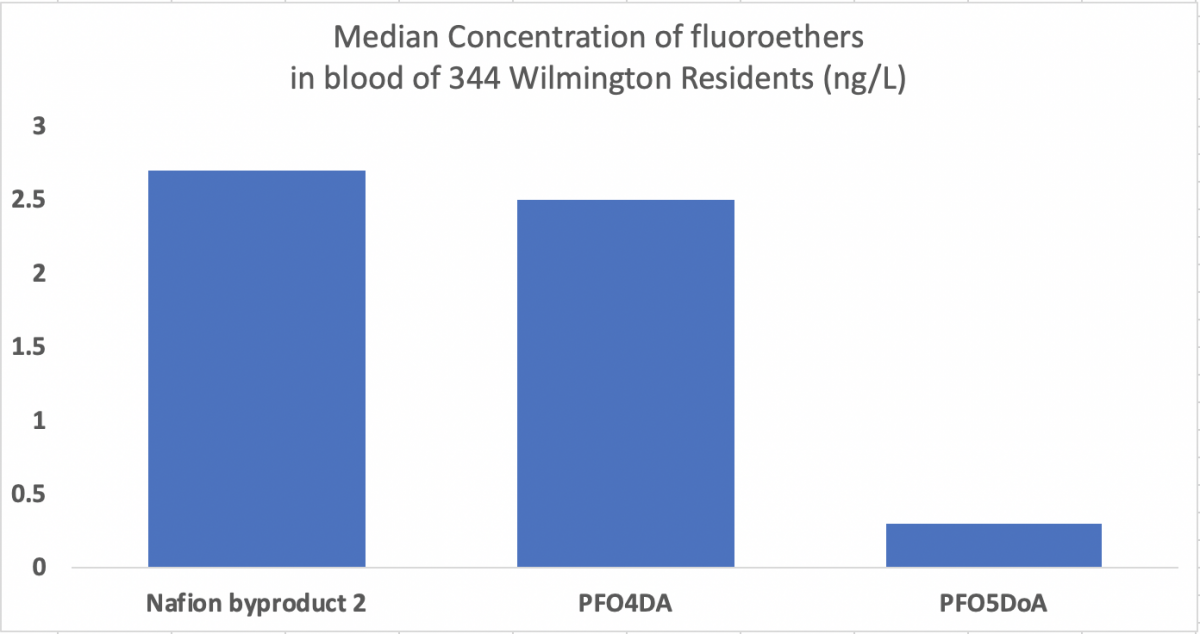

- Ten PFAS were found in most of the blood samples. Four of these were fluoroethers (Nafion byproduct 2, PFO4DA, PFO5DoA, and Hydro-Eve) which are unique to the chemical facility. These chemicals were previously detected in the Cape Fear River downstream of the facility [Figure 1]. It is likely that the main way people got some fluoroethers in their bodies was through drinking water from the Cape Fear River.

- Even though almost everyone’s blood had fluoroethers in it (99% of people had at least one fluoroether detected), GenX was not found even though it was reported in the drinking water. Overall in this group, 25% of the total measured PFAS was from the fluoroethers.

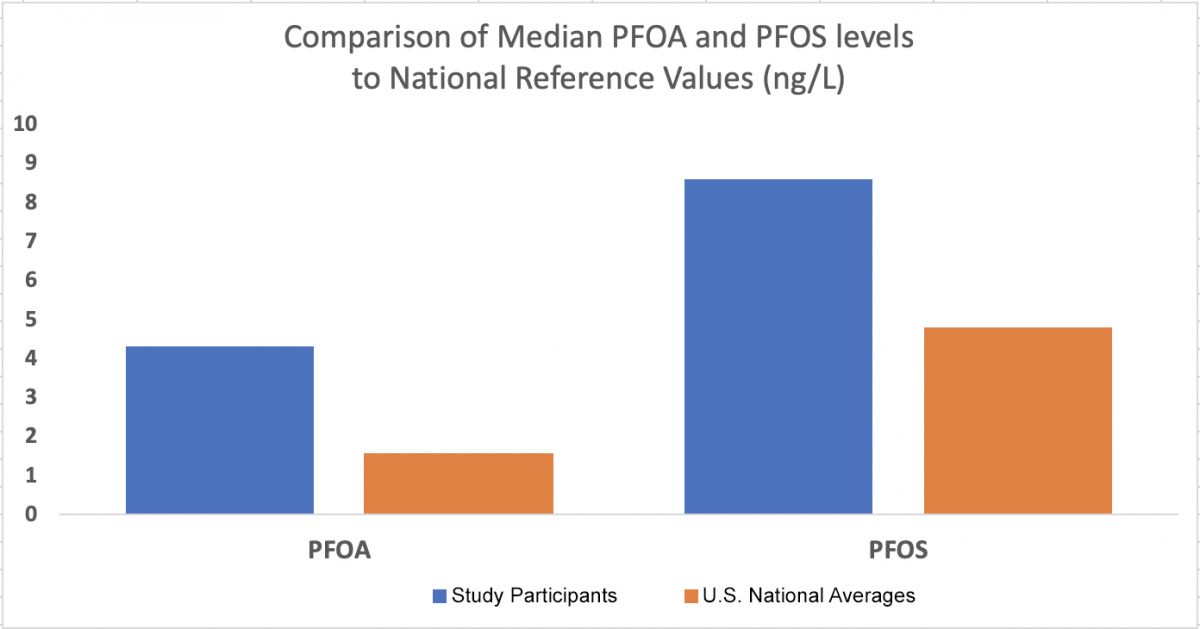

- Almost everyone’s blood had legacy PFAS in it. Study participants had much higher levels of the legacy PFAS in their blood than U.S. national averages. The higher levels of legacy PFAS may be a result of many sources of exposure [Figure 2].

- Fluoroethers seem to leave the body faster than legacy PFAS.

This paper did not evaluate potential health outcomes related to PFAS exposure. Future studies will explore that topic.

For more information on the GenX Exposure Study, please visit our website: GenXStudy.ncsu.edu.

This study was done by scientists and community partners from North Carolina State University, East Carolina University, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, New Hanover County Health Department, and Cape Fear River Watch. This research was funded by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (1R21ES029353), the Center for Human Health and the Environment (CHHE) at North Carolina State University (P30ES025128), and the NC Policy Collaboratory.